Histologic and Cytologic Diagnosis

Safe, minimally invasive techniques have been developed to definitively

diagnose most digestive disorders, including the acquisition of cytologic or

histologic specimens. This has been particularly important in malignant

disease, where it is rarely, if ever, acceptable to consider treatment without

first making a “tissue diagnosis.” In many more cases, cytology or pathology

obtained by endoscopy can exclude a malignancy or diagnose a malignancy that

does not require surgical intervention (e.g., gastric mucosa-associated

lymphoid tissue [MALT] lymphomas, which are treated with antibiotics;

malignancies that are diffusely metastatic and therefore beyond the benefit of

surgery).

In many situations, highly accurate

photo documentation may be a most valuable tool in making the diagnosis and

guiding therapy. Much more often, however, biopsies are essential, even at

times when the gross appearance is normal. Common examples of this in the upper

gastrointestinal tract include eosinophilic esophagitis and celiac disease.

Histology can also determine the cause of what may appear to be mild

nonspecific erythema to reveal that it is due to an infection or Crohn disease.

Histologic specimens obtained by endoscopic biopsies or cytologic specimens

provided by brushes or fine-needle aspiration provide the clinician with definitive

data with which an effective therapeutic strategy can be designed.

When receiving the results of a

procedure, the ordering clinician should clarify whether biopsies or cytologic

specimens were taken and the number of specimens taken. Providing the

pathologist with a sufficient number of specimens to make a definitive diagnosis

is a key quality metric. It is rarely, if ever, appropriate to take fewer than

three specimens; taking this number does not increase the number of passes of

the forceps (time) needed or the expense of the procedure. Endoscopists should

also be adept at directing the biopsy forceps. Receiving an endoscopic report

with photo documentation of an abnormality but with a pathology report that is

read as normal should raise concern. The specimen should be taken with an

optimal orientation. Taking biopsies tangentially to the orientation of the

mucosa makes it difficult to provide a definitive and accurate diagnosis.

Orientation is particularly important in the duodenum, where the biopsy should

be obtained across a fold (plicae circulares) and perpendicular to the mucosa

to accurately assess villous height and crypt depth, as is critical in

assessing the diagnosis and severity of small intestinal mucosal diseases such as

celiac disease.

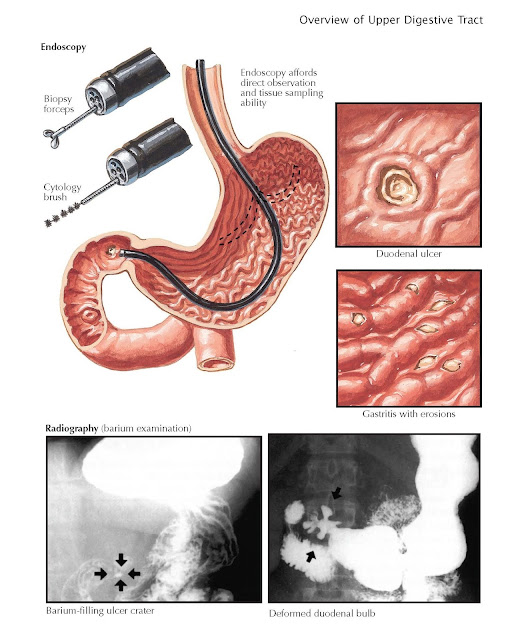

Most exfoliated cytologic specimens

are obtained by endoscopically guided brush cytologic procedures or

interventional radiology experts. Abrasive brush devices for obtaining tissue

for cytologic diagnoses, including an intraesophageal brush, have been proposed

as a less invasive means of diagnosing esophageal disorders. Although the risk

is lesser than with endoscopy, the procedure rarely provides definitive data

for treatment and management. Potential limitations of guided fineneedle aspirations,

whether obtained by EUS or radiology, include the risk of discomfort or

bleeding; even multiple passages of the needle may not provide adequate

cellular data. The risk of inadequate cellular data can be reduced by having a

cytology expert in the procedure room to assess the quality of such specimens.

The problem of being able to provide

definitive histologic or cytologic information for guiding treatment occurs all

too commonly with the myriad of functional gastrointestinal disorders for which

no histologic or cytologic specimen can provide a definitive diagnosis. These

disorders are particularly challenging because they are common, lead to

substantial degradation in the quality of life, and lead to a loss of

productivity and success at school or work, but they almost never lead to

serious complications or shortening of the life span. The astute clinician must

use judgment based on the risk of finding an alternative diagnosis,

particularly a life-threatening disease, to determine whether the taking of

endoscopic photographs or histologic or cytologic specimens is warranted. To

aid in this decision, various alarm signs and symptoms have been identified for

most symptom complexes. These include symptoms that persist after effective

therapy or that interrupt sleep; age over 45 years; the presence of fever,

weight loss, nausea and vomiting, or anemia; or gross blood loss. Experts have

also identified a number of criteria by which a diagnosis of a functional

disorder can be made without ordering unnecessary testing, most notably the

ROME criteria. Although they are not without controversy, such approaches provide

a means by which excessive endoscopic and radiologic testing can be minimized.