Sunday, May 11, 2025

Friday, April 25, 2025

TRAUMA TO PENIS AND URETHRA

Sunday, April 20, 2025

CYSTS AND CANCER OF THE SCROTUM

Tuesday, November 19, 2024

Delayed Or Absent Puberty

Saturday, September 30, 2023

INTERSEX FEMALE PSEUDOHERMAPHRODITISM

Sunday, March 26, 2023

Tuesday, March 21, 2023

Lactation

Monday, March 20, 2023

Prenatal Screening and Diagnosis

Wednesday, February 15, 2023

Fertilization And The Establishment Of Pregnancy

Tuesday, February 14, 2023

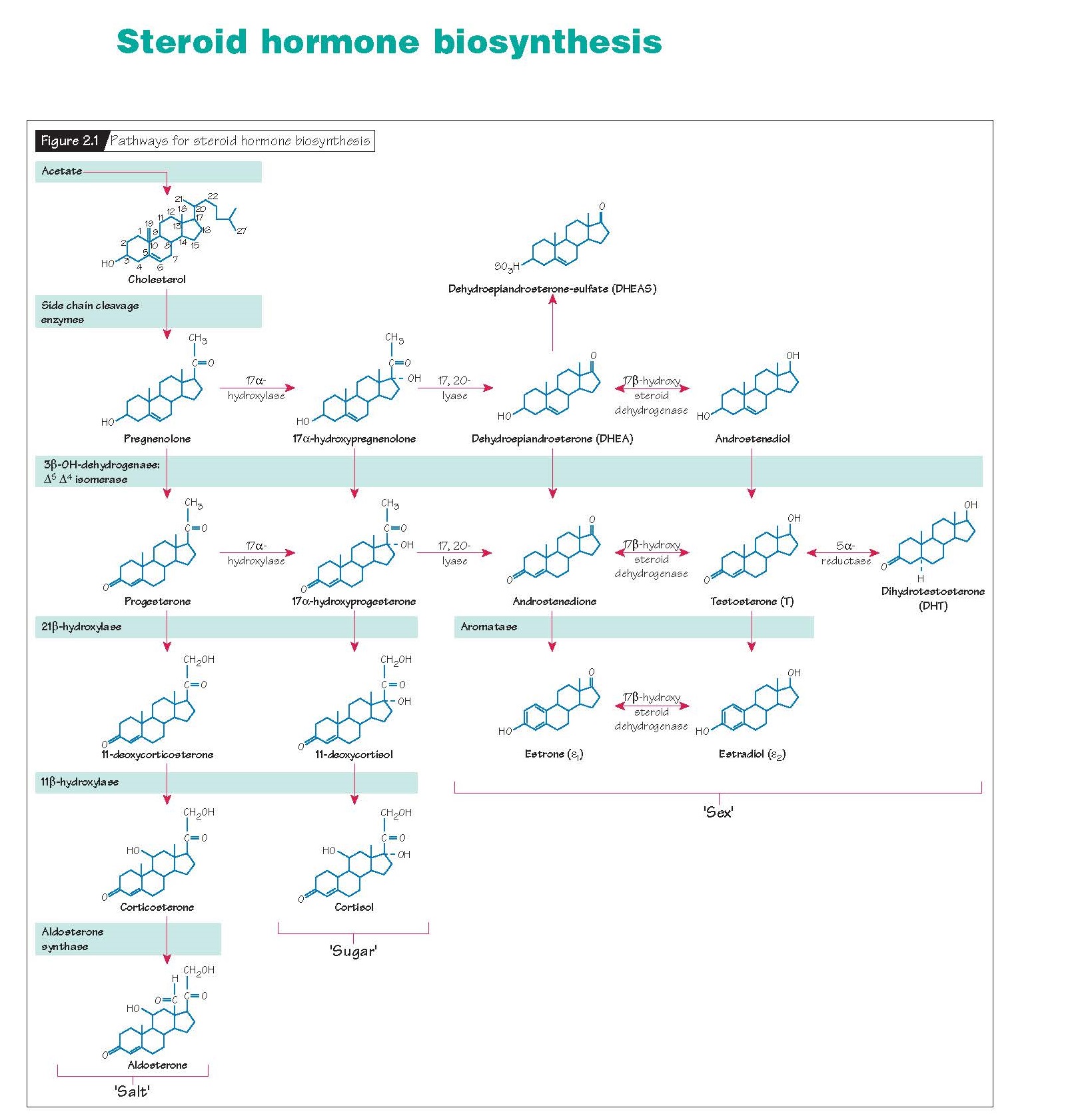

Steroid Hormone Biosynthesis

Thursday, February 2, 2023

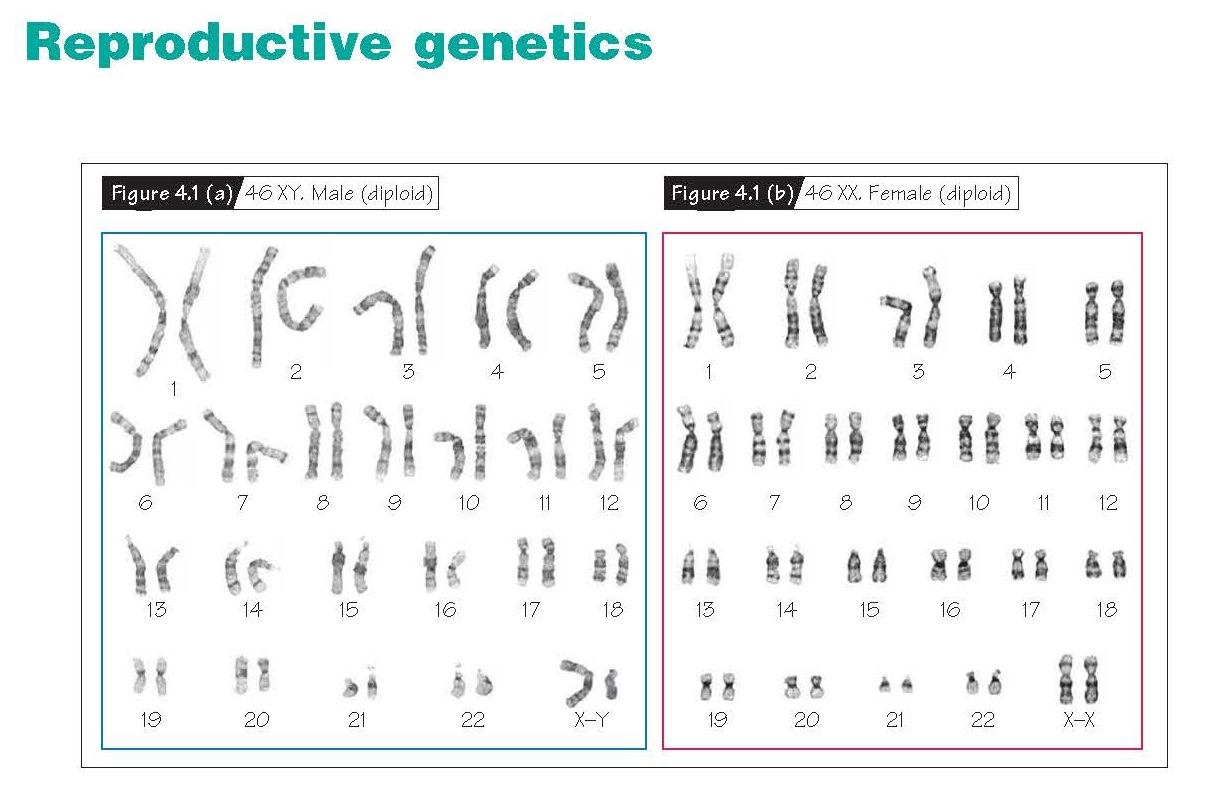

Reproductive Genetics

Tuesday, January 31, 2023

Musculoskeletal System: Limbs

Skeletal System

Wednesday, December 1, 2021

PUERPERAL INFECTION

PUERPERAL

INFECTION

Puerperal infection generally refers to an infection of the genital

tract in the postpartum period. For centuries, puerperal infection was the

leading cause of maternal death, though this has changed dramatically with the

advent of antibiotics. Maternal death rates associated with infection account

for approximately 0.6 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. Endometritis is

the most common form of postpartum infection, though other sources of

postpartum infections include postsurgical wound infections, perineal

cellulitis, mastitis, respiratory complications from anesthesia or under-lying

pulmonary disease such as asthma or obstructive lung disease, retained products

of conception, urinary tract infections, and septic pelvic phlebitis. Overall,

postpartum infection is estimated to affect 1% to 3% of normal vaginal

deliveries, 5% to 15% of scheduled caesarean deliveries, and 15% to 20% of

unscheduled caesarean deliveries.

The organisms responsible for the vast majority of puerperal infections are the anaerobic and aerobic nonhemolytic varieties of streptococci. These organisms are usually present in the birth canal, becoming pathogenic when carried to the uterine cavity during or after delivery.

ERYTHROBLASTOSIS FETALIS (RH SENSITIZATION)

ERYTHROBLASTOSIS

FETALIS (RH SENSITIZATION)

Isoimmunization of the mother to any dissimilar

fetal blood group not possessed by the mother is possible. Historically the

most common example is the Rh (D) factor. Erythroblastosis fetalis (hemolytic

disease of the newborn) is characterized by sustained destruction of the fetal

erythrocytes by specific maternal antibodies (IgG), which cross the placenta to

the fetus. What was once a common cause for fetal death has largely been

eradicated by prophylactic maternal administration of immune globulin against

the Rh (D) factor to those at risk.

Human red blood cells contain a complex group of inherited antigens, one of which is the Rhesus CDE antigen system. The genes for the CDE blood groups are inherited separately from the ABO groups and are located on the short arm of chromosome 1. One of the more important antigens of this group is Rh (D) factor. About 85% of all individuals are Rh (D)-positive whereas 15% are Rh (D)-negative. Any process that exposes the woman to blood carrying the D antigen including blood transfusion, miscarriage, ectopic or normal pregnancy, trauma during pregnancy, amnio-centesis, and others can result in anti-Rh agglutinins being formed. The IgG antibodies can cross the placenta into the fetal circulation and result in the destruction of the Rh-positive fetal blood. Other isoimmunizations (most frequently Kell, or Duffy antigens) can also result in similar effects on the fetus.

SYPHILIS

SYPHILIS

In

many geographical regions, syphilis is still the most common cause of fetal

death in the later months of gestation. In many developed countries, the number

of primary and secondary syphilis cases rose dramatically during the late 1980s

and early 1990s (peak 1991) as a result of illicit drug use and the exchange of

drugs for sex. Although rare in developed countries, the incidence of syphilis

is high and increasing in many developing countries (and in the transitional

economies of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union), particularly where

HIV/AIDS is common. Of infants born to mothers with primary or secondary

syphilis, up to 50% will be premature, stillborn, or die in the neonatal

period. In many cases, surviving children are born with congenital defects some

of which may not be apparent for years.

The fetus is infected through the placenta from the mother. When an infected fetus is born alive, the symptomatology of congenital syphilis soon becomes manifest. While appropriate treatment of the mother can prevent congenital syphilis, the inability to effectively identify infected patients and get them to undergo treatment continues to present a challenge to reducing the incidence of syphilitic complications. Screening in the first trimester with nontreponemal tests such as rapid plasma reagin or Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test combined with confirmation of reactive individuals with treponemal tests such as the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) assay is a cost-effective strategy. Those at risk should be retested in the third trimester.

INTRAUTERINE GROWTH RESTRICTION

INTRAUTERINE

GROWTH RESTRICTION

Symmetric or asymmetric reduction in the size

and weight of the growing fetus in utero, compared with that expected for a

fetus of comparable gestational age, constitutes intrauterine growth

restriction. This reduced growth may occur for many reasons, but most

occurrences represent signs of significant risk of fetal death or jeopardy to

the fetus. Some authors advocate identifying fetuses with growth between the

10th and 20th percentiles as suffering “diminished” growth and at intermediate

risk for complications. Problems of consistent definition make estimates of the

true prevalence of growth restriction difficult, but by most definitions it

occurs in 5% to 10% of pregnancies.

The risk of intrauterine growth restriction increases with the presence of maternal conditions that reduce placental perfusion (hypertension, preeclampsia, drug use, smoking) or those that reduce the nutrients available to the fetus (chronic renal disease, poor nutrition, inflammatory bowel disease). Abnormalities of placental implantation or function can result in significant reduction in nutrient flow to the fetus. The risk is also higher at the extremes of maternal age: for women less than 15 years old the rate of low birth weight is 13.6% compared with 7.3% for women between 25 and 29 years old. When multiple gestations are excluded, the rate for women older than 45 years is greater than 20%. Multiple pregnancies, especially higher order multiples, are at increased risk for growth restrictions. In most cases of growth restriction, no specific cause is identified.

CAUSES OF DECREASED MATERNAL CIRCULATION

CAUSES

OF DECREASED MATERNAL CIRCULATION

Various pathologic conditions may impede the

maternal circulation to the placenta. They can be grouped as follows:

1. Diseases

of the uterine vessels: (a) acute atherosis, (b) arteriolar sclerosis associated with

essential hypertension, and (c) inflammation (angiitis) associated with

chorioamnionitis.

2. Premature

separation of the placenta associated with retroplacental hemorrhage or

inflammatory exudation.

3. Conditions

that may cause an increase in intra-uterine pressure: (a) multiple pregnancy,

(b) macrosomia, (c) polyhydramnios, and (d) hydatidiform mole.

4.

Extensive

thrombosis of the intervillous space or of the marginal sinus.

5.

Death

of the mother.

The most common cause of placental infarcts in cases of preeclampsia have been found to be acute atherosis of the decidual vessels. This lesion is manifested microscopically as a deposition of lipids, in the intima of decidual arterioles and endometrial arteriovenous lakes. Part of the material is doubly refractive under polarized light and occurs both extracellularly and inside lipophages. The lesions closely resemble acute fulminating atherosis in other settings. The process leads to marked intimal thickening and vascular occlusion. The lesions occur in the decidua vera, as well as in the basalis, but they do not involve to a comparable degree the vessels of the myometrium or other tissues in the body. Fat stains have not revealed the lesion in fetal vessels. Contiguous trophoblastic tissue seems to be a necessary factor in its pathogenesis. The lesions regress promptly after delivery. The cause of this condition is still unknown.

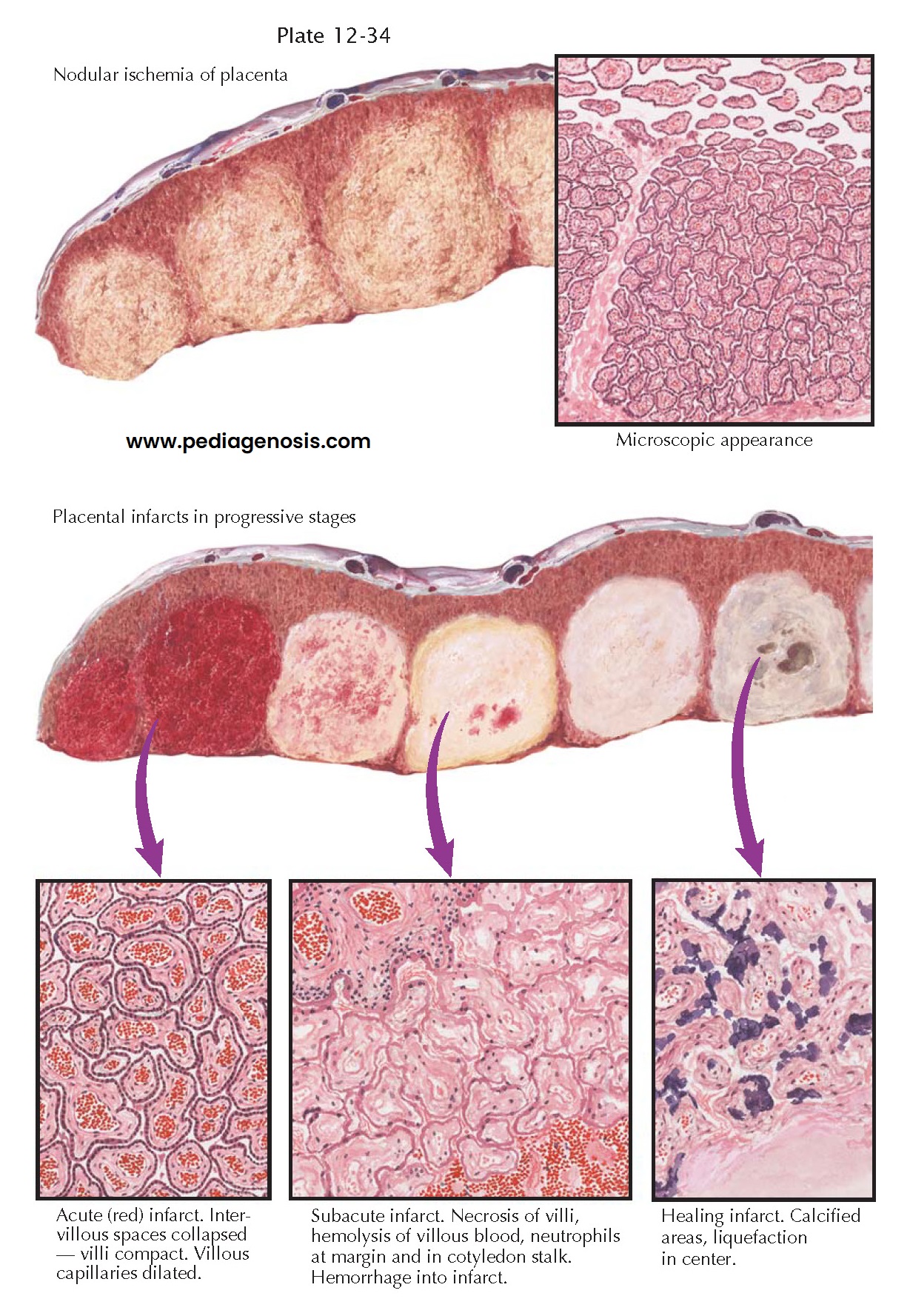

PREECLAMPSIA IV-PLACENTAL INFARCTS

PREECLAMPSIA

IV-PLACENTAL

INFARCTS

Because preeclampsia is a

condition peculiar to pregnancy, and because delivery usually results in the

rapid regression of the signs, symptoms, and pathologic lesions, it would seem

reasonable to believe that the contents of the gravid uterus either may be the

source of the vasoconstrictor factor or may play an important role in leading

to the production of that factor elsewhere in the body. The fetus is not a

required factor, because severe preeclampsia occasionally accompanies

hydatidiform mole. Therefore, the trophoblastic tissue or the gravid

endometrium would seem to be incriminated. Despite this, there are no micro- or

macroscopic placental lesions that are pathognomonic for preeclampsia.

Pathologic studies have revealed close correlation between the occurrence of preeclampsia and conditions that are prone to cause a decrease in the maternal circulation to the placenta, to the decidua, or to both of these tissues. Obstruction of the maternal blood flow to one or more placental cotyledons causes true infarction of the involved areas. Unfortunately, the term infarct has often been used for a wide variety of nodular lesions in the placenta, and conflicting opinions have been expressed concerning the association of such lesions with preeclampsia.

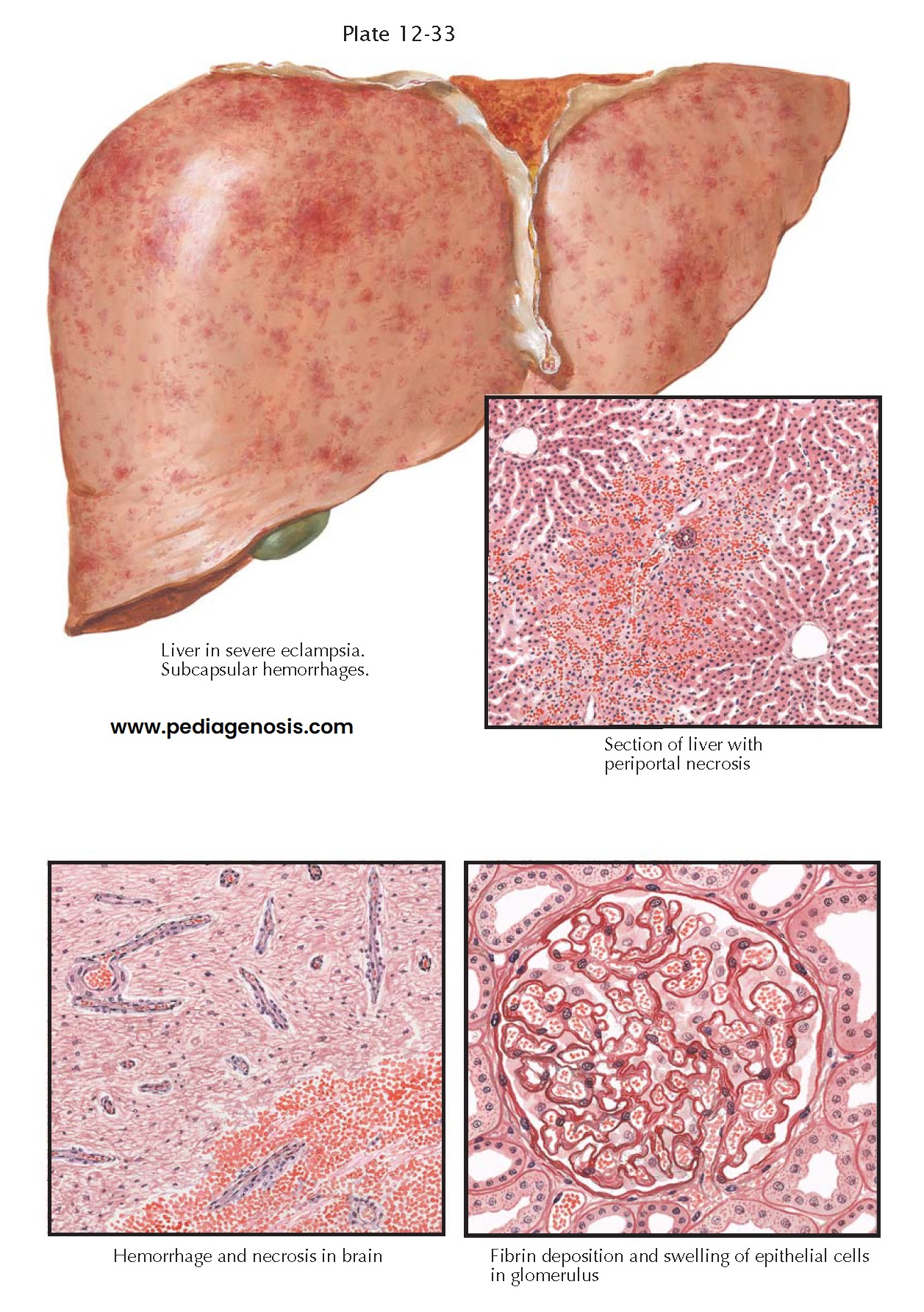

PREECLAMPSIA III—VISCERAL LESIONS IN PREECLAMPSIA AND ECLAMPSIA

PREECLAMPSIA

III—VISCERAL LESIONS IN PREECLAMPSIA AND ECLAMPSIA

Although preeclampsia and eclampsia are

differentiated, depending upon whether or not the patient has had a convulsion,

the pathology of the two is essentially the same. Characteristic lesions

frequently appear in the liver, kidneys, and brain, but they are inconstant in

occurrence and may be absent even in severe cases with convulsions. Therefore,

they cannot be considered primary lesions but are probably the sequelae of the

three constantly present features of the disease, namely, vasoconstriction,

hypertension, and fluid retention.

In typical cases, the liver is swollen and mottled with small hemorrhages. Microscopically, the sinusoids around the smaller portal areas are plugged with fibrinoid material and surrounded by foci of hemorrhage and necrotic liver cells. Occasionally, midzonal necrosis is seen, but serial sections usually reveal continuity with larger periportal lesions. The condition may be wide- spread or may involve only a few subcapsular lobules.