Gastrointestinal

Tract: Overview And The Mouth

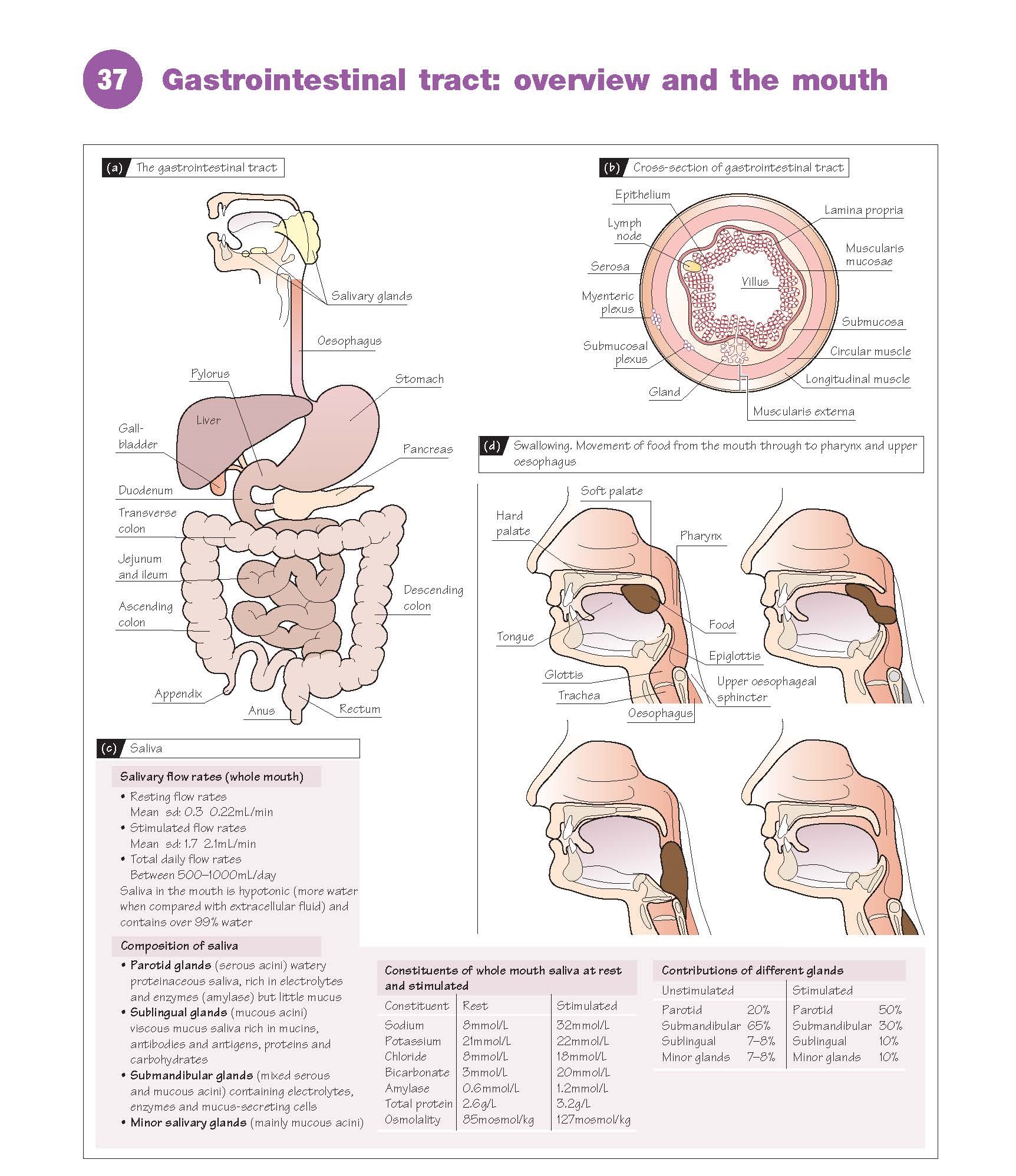

The gastrointestinal

(GI) tract is responsible for the breakdown of food into its component parts so that they can

be absorbed into the body. It is made up of the mouth, oesophagus,

stomach and small and large intestines. The salivary glands,

liver, gallbladder and pancreas are organs distinct from

the GI tract, but all secrete juices into the tract and aid the digestion

and absorption of

the food (Fig. 37a).

Structure

Different regions of the tract are

concerned with motility (transport), storage, digestion, absorption

and elimination of waste, and these functions of the GI tract are

controlled by neuronal, hormonal and local regulatory

mechanisms.

The walls of the GI tract have a

general structure that is similar along most of its length, although this is

modified as function varies. This basic structure is shown in Figure 37b. It

comprises the mucosal layer, made up of epithelial cells (which can be

involved in either the process of secretion or absorption depending on their

location in the GI tract), and the lamina propria, consisting of loose

connective tissue, collagen and elastin, blood vessels and lymph tissue, and a

thin layer of smooth muscle called the muscularis mucosa which, when

contracting, produces folds and ridges in the mucosa. The submucosal layer comprises

a second layer of connective tissue, but also contains larger blood and

lymphatic vessels and a network of nerve cells called the submucosal plexus (Meissner’s

plexus). This is a dense plexus of nerves innervated by the autonomic part

of the nervous system which can function as an independent nervous system – the

enteric nervous system. Below the submucosa is the muscularis externa.

This comprises a thick circular layer of smooth muscle around the GI

tract which, when it contracts, produces a constriction of the lumen. Below

this layer of muscle is another thinner layer of muscle arranged in a longitudinal

manner which, when it contracts, results in shortening of the tract.

Between these two layers of muscle is a second nerve plexus, called the myenteric

plexus (Auerbach’s plexus), which is also part of the enteric

nervous system. The outermost layer of the GI tract is the serosa,

another connective tissue layer covered with squamous mesothelial cells.

Saliva and mastication

The GI tract starts in the mouth,

where food is initially chewed (masticated) and mixed with

salivary secretions. Mastication is the process of systematic mechanical

breakdown of food in the mouth. The amount of mastication necessary in order to

swallow the food depends on the nature of the ingested food: solid foods are

subjected to vigorous chewing, whereas softer foods and liquids require little

or no chewing and are transported almost directly into the oesophagus by

swallowing. Mastication is necessary for some foods, such as red meats, chicken

and vegetables, to be fully absorbed by the rest of the GI tract. However,

fish, eggs, rice, bread and cheese do not require chewing for complete

absorption in the tract.

Mastication involves the

coordinated activity of the teeth, jaw muscles, temporomandibular joint, tongue and other structures,

such as the lips, palate and salivary glands. The forces

developed between the teeth during mastication have been measured to be about

150–200 N; however, the maximum biting force developed between the molar teeth

is almost 10 times this value.

During mastication three pairs of

glands, the parotid, submandibular and sublingual, secrete

saliva. The major functions of saliva are to moisten and lubricate the

mouth at rest, but particularly during eating and speech, to dissolve food

molecules so that they can react with gustatory receptors giving rise to the

sensation of taste, to ease swallowing, to begin the early part of digestion

of polysaccharides (complex sugars) and to protect the oral cavity

by coating the teeth with a proline-rich protein or pellicle that can serve as

a protective barrier on the tooth surface. Saliva also contains immunoglobulins

that have a protective role in avoiding bacterial infections.

Saliva is hypotonic and

contains a mixture of

both inorganic and organic

constituents. The composition varies according to which gland is secreting and

also whether it is resting or being stimulated (Fig. 37c).

The control of salivary

secretion depends on reflex responses which, in humans, have been shown to

be elicited by the stimulation of gustatory (taste) receptors and periodontal

and mucosal mechanoreceptors during mastication. Although it was thought that

olfactory afferent stimulation (smell) also had a general reflex effect on

salivary secretion, it has now been shown that this reflex operates via the

submandibular/sublingual glands and not the parotid in humans. The sight and

thought of food in humans have very little effect on salivary production. The

perception of an increased salivary production is thought to be related to the

sudden awareness of saliva already present in the mouth.

Swallowing

Swallowing occurs in a number of phases. The first phase

is voluntary and involves the formation of a bolus of food by chewing

and tongue movements (backwards and upwards), which push the food into the

pharynx. The remaining phases are not voluntary, but reflex responses initiated

by the stimulation of mechanoreceptors with afferents in the glossopharyngeal

(IX) and vagus (X) nerves to the medulla and pons (brain stem); here, there

is a group of neurones (the ‘swallowing centre’) which coordinates the

complex sequence of events that eventually delivers the bolus into the

oesophagus. The soft palate elevates to prevent food from entering the nasal

cavity, respiration is inhibited, the larynx is raised, the glottis

is closed and the food pushes the tip of the epiglottis over the

tracheal opening, preventing food from entering the trachea. As the bolus

enters the oesophagus, these changes reverse, the larynx opens and breathing continues (Fig. 37d).