UROLITHIASIS

Renal stones are common, with lifetime prevalence estimates as high as 15%. Historically, men are affected more often than women, with a ratio of 2 or 3:1, although recent evidence suggests the gender gap may be closing. Stones can form at any age, but most occur in adults between 30 and 60 years of age. The clinical and economic impact of stone disease is substantial, with an estimated $2 billion spent in the United States in 2000.

Bladder stones are also associated with significant

morbidity but occur far less frequently than renal stones. Because the causes

of renal and bladder stones are distinct, their associated symptoms,

treatments, and prevention strategies are considered separately.

RENAL STONES

Pathogenesis. The majority

of renal stones (80%) are calcium-based, most frequently calcium oxalate and

less commonly calcium phosphate. Other less common stone compositions are uric

acid, struvite, and cystine. When stone-forming salts reach a urinary

concentration that exceeds the point of equilibrium between dissolved and

crystalline components, crystallization will occur. Although certain chemicals

in the urine can delay stone formation, there is a concentration of

stone-forming salts above which crystallization becomes inevitable. Thus

factors that increase the propensity for stone formation do so by reducing

urine volume, increasing the quantity of stone-forming salts, or decreasing the

quantity of crystallization inhibitors.

The process by which crystal formation leads to stone

formation remains incompletely understood. Recent evidence, however, suggests

that routine calcium oxalate stones originate on calcium phosphate deposits,

known as Randall plaques, that are located at the tips of renal papillae and

act as niduses for crystal overgrowth.

Risk Factors. Calcium stones

are associated with a variety of genetic, environmental, and dietary risk

factors. Elevated urinary calcium levels, one of the most common causes of

calcium stones, can occur in the setting of increased bone resorption,

intestinal hyperabsorption of calcium, or impaired renal tubular reabsorption

of calcium. Elevated urinary oxalate levels, either dietary or the result of

enhanced intestinal oxalate absorption, increase the urinary saturation of

calcium oxalate and promote stone formation.

Depressed urinary citrate levels, often idiopathic but

in some cases associated with systemic acidosis or hypokalemia, are also

associated with an increased risk of calcium stones because citrate is an

important inhibitor of stone formation. Finally, elevated urinary uric acid

levels promote calcium oxalate stone formation and are associated with

excessive intake of animal protein, conditions that lead to

overproduction/overexcretion of uric acid (e.g., Lesch-Nyhan syndrome), or use

of uricosuric medications.

Noncalcium stones are also associated with specific

metabolic, genetic, and infectious disorders. Uric acid stones primarily occur

in the setting of overly acidic urine, in which uric acid crystallizes. These stones are more common

among patients with insulin resistance and type II diabetes mellitus, in whom

production and excretion of ammonia in the renal proximal tubule is impaired,

leading to insufficient buffering of protons in urine. Magnesium ammonium

phosphate (struvite) stones, in contrast, occur in the setting of overly

alkaline urine, in which struvite and calcium carbonate precipitate. These stones primarily occur in patients

who have urinary tract infections with urea splitting bacteria, such as Proteus, Pseudomonas, Klebsiella,

and Staphylococcus. The hydrolysis of urea produces high concentrations

of ammonia, which buffers protons. Incorporation of bacteria into these stones

may cause chronic infections. Finally, cystine stones occur because of an

inherited disorder of amino acid transport in which proximal tubular reabsorption of dibasic amino acids (cystine,

lysine, ornithine, arginine) is impaired, leading to high urinary

concentrations. Because cystine is poorly soluble in urine, it crystallizes and

forms stones at relatively low urinary concentrations.

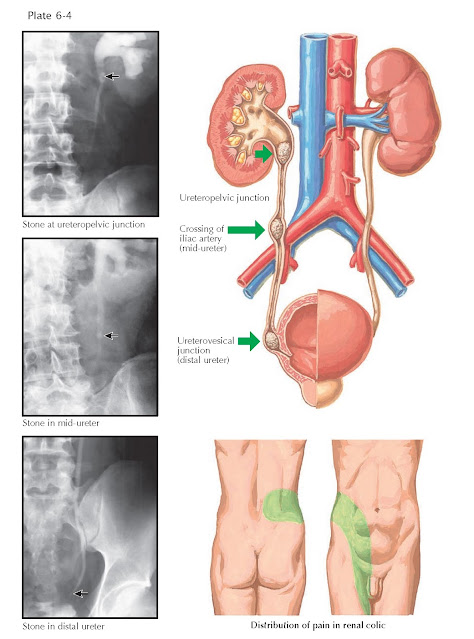

Presentation and Diagnosis. The symptoms associated with renal stones depend on their location.

Typically, stones located within the calyces are asymptomatic. When these

stones become detached and are propelled down the narrow ureter, however, they

frequently become impacted. Stones generally become lodged in the narrowest

portions of the ureter, which are located at the ureteropelvic junction, the

crossing of the iliac vessels, and the ureterovesical junction (see Plate 6–4).

The first sign of a stone in the ureter is often the acute onset of severe flank

pain. The stone obstructs urine outflow from the kidney, and the acute increase

in renal pelvic pressure causes distention of the collecting system and

stretching of the renal capsule, producing pain that classically starts in the

flank and radiates to the ipsilateral groin. For reasons that are incompletely

understood, the pain of a ureteral stone is typically intermittent, rather than

constant. Other symptoms include nausea, vomiting, and gross or microscopic

hematuria. This constellation of symptoms is known as renal colic.

Occasionally, the movement of a stone into the ureter can be associated with

obstruction and infection, culminating in pyelonephritis (see Plate 5–5) and/or

sepsis. In this situation, urgent relief of obstruction is required to

decompress the collecting system and allow antibiotics to be excreted into the urine.

Most renal stones can be detected on plain abdominal

radiographs because of their calcium content, although calcium-poor stones such

as pure uric acids stones are radiolucent. The primary diagnostic imaging tool,

however, is non–contrast enhanced CT, which has a 98% sensitivity for the

detection of stones. If intravenous contrast is administered and excreted into

the urine collecting system, stones may be obscured, since both stones and

contrast have high attenuation.

If a stone is identified, microscopic analysis of urine

may be helpful to determine stone composition, as characteristic crystals are

sometimes seen.

|

| MAJOR SITES OF RENAL STONE IMPACTION |

Treatment. The treatment

of a renal stone depends on its size, location, and associated symptoms. The

majority of stones that enter the ureter will pass on their own, given enough

time. The likelihood of spontaneous stone passage is higher for stones that are

small and/or located in the distal ureter. The time interval to stone passage

is variable, and intermittent episodes of pain may accompany stone transit.

Once they reach the bladder, most stones can easily be voided, as the lumen of

the urethra is much larger than that of the ureter.

Medications such as calcium channel blockers and -receptor antagonists have been shown to influence

ureteral contractility and promote stone passage, thereby increasing the

likelihood of spontaneous passage, reducing the time interval to passage, and

decreasing the need for pain medication. A trial of these medications is

indicated in patients with ureteral stones less than 1 cm in size, particularly

if they are located in the lower part of the ureter at the time of diagnosis.

When a ureteral stone fails to pass or is too large to pass, or when pain becomes intolerable, surgical

intervention is warranted. Many small to moderate-sized stones can be treated

noninvasively, using shock waves focused on the stone under fluoroscopic or

ultrasound guidance (extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy, see Plate 10-12).

Repeated application of focused shock-waves causes stone fragmentation, which

enables painless passage of fragments in the urine. Alternatively, stones can

be removed using a ureteroscope (see Plate 10-33), which is passed through the urethra and bladder up to the site

of the stone in the ureter. The stone is then fragmented with a laser or other

device inserted through the working channel of the ureteroscope.

For large and/or complex stones, such as staghorn

calculi (which occupy all or a large portion of the collecting system), a large

endoscope is introduced percutaneously into the kidney through a small incision

in the flank. The stone is then fragmented and the fragments removed (percutaneous nephrostolithotomy, see Plate 10-13).

Prognosis. After a first

renal stone is diagnosed, there is a nearly 50% likelihood of recurrence over

the next 5 to 10 years. With medical and dietary therapy, however, the

recurrence rate can be significantly reduced.

Prevention strategies generally aim to correct under-lying risk factors with diet or medication. Dietary changes that can lower the

risk of calcium stones include an increase in fluid intake (sufficient to produce

a urine volume of >2 L daily), limitation of salt intake (which reduces urinary

calcium excretion), modest restriction of animal protein, and a reduction in

consumption of oxalate-rich foods (such as nuts, chocolate, brewed tea, and

dark green leafy vegetables). Severe dietary calcium restriction is discouraged

in any stone former, but for patients with elevated urinary calcium levels, a

modest reduction in calcium intake is recommended.

Medications can also help prevent stone formation. For

patients with calcium stones, thiazide diuretics can help reduce urinary

calcium excretion. For patients with uric acid stones, alkalizing agents such

as potassium citrate can increase uric acid solubility. In the minority of

patients with elevated urine uric acid levels, allopurinol may also be used.

Finally, underlying medical disorders that favor stone

formation should also be treated, such as hypercalcemia associated with

hyperparathyroidism.

BLADDER STONES

Primary bladder stones form within the bladder and are

distinct from stones that originate in the kidney and pass into the bladder.

Although bladder stones were common in the past, improvements in nutrition have

substantially reduced their incidence, since dietary phosphate deficiency and

excess ammonia excretion can contribute to stone formation. In developing

countries, however, bladder stones remain common.

In industrialized nations, bladder stone formation is

usually related to urinary stasis or urinary infection with urea-splitting

bacteria (e.g., Proteus mirabilis). Indeed, these conditions often

coexist, since urinary stasis predisposes to infection. Bladder stones are

typically com- posed of calcium phosphate, uric acid, or struvite.

The most common disorder associated with incomplete

bladder emptying and bladder stone formation is benign prostatic hyperplasia

(BPH). In affected patients, treatment consists of transurethral prostate

resection and laser or pneumatic stone fragmentation. In the case of a very

large prostate, open prostatectomy and bladder stone removal may be necessary.

Another disorder associated with bladder stone

formation is neurogenic bladder (see Plate 8-2), which occurs when neurologic

disorders such as spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, or spina bifida

interfere with normal voiding. Patients with neurogenic bladder who have long-term

indwelling catheters are particularly prone to bladder calculi because of their

increased rate of

infection with urea-splitting organisms. The bladder stones are most commonly treated with endoscopic fragmentation

and removal, with open surgery only rarely performed. The risk of further stone

formation can be decreased with intermittent rather than indwelling

catheterization, increased hydration, and bladder irrigation with weakly acidic

solutions, such as acetic acid. Antibiotics are rarely indicated because

bacteriuria is essentially unavoidable, and overuse of anti- biotics may

promote resistance.

The symptoms of bladder calculi are typically less

obvious than those associated with kidney stones. Some patients may be

completely unaware that they have a stone, while others may complain of urgency

and frequency of urination, pelvic pain, or hematuria. These symptoms are also

commonly associated with the underlying condition that leads to stone

formation, such as bladder outlet obstruction or bladder infection.