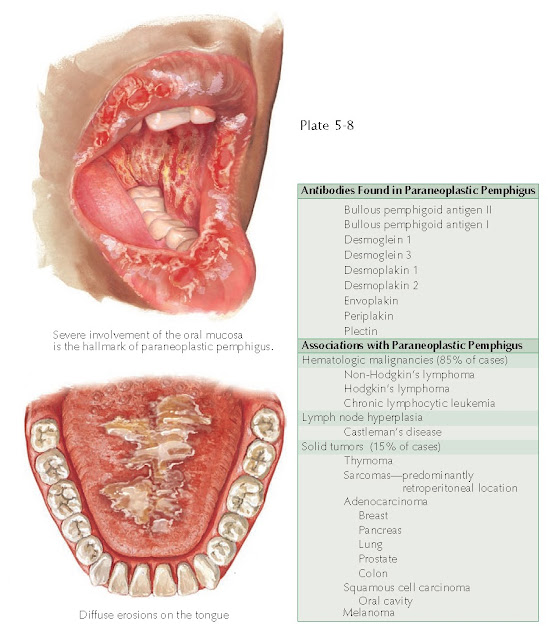

PARANEOPLASTIC PEMPHIGUS

Paraneoplastic pemphigus was not described until the early 1990s. It is a rare subset of the pemphigus family of diseases that is associated with the synchronous occurrence of a systemic neoplastic process. The neo-plastic disease may precede the diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus. This disease has been differentiated from other forms of pemphigus by its unique antibody profile and staining patterns. Most cases have occurred secondary to hematological malignancy, but solid tumors have also been with paraneoplastic pemphigus.

Clinical

Findings: Paraneoplastic pemphigus is most likely to occur in the older

population, usually during the seventh or eighth decade of life. It has also

been reported to occur in young children with neoplastic disease. There is no

sex or race predilection. Most patients develop paraneoplastic pemphigus after

the diagnosis of an internal malignancy or at the same time as their diagnosis.

The oral mucosa is almost always the first

mucocutaneous surface to be affected. Severe erosions and ulcerations occur

throughout the oropharynx. This leads to significant pain and difficulty

eating. Patients avoid eating because of the severe, unremitting pain. Weight

loss and blistering, in combination with the underlying malignancy, result in a

severe, life-threatening illness. The hallmark of this disease is the severe

oral mucous membrane involvement. In fact, if the patient does not have oral

involvement, the diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus should be reevaluated,

and the patient most likely has another form of pemphigus. Soon after the onset

of oral disease, the patient’s skin begins to break out in vesicles and flaccid

bullae. These blisters are identical to those seen in pemphigus vulgaris.

Histologically, there are some subtle differences in immunofluorescence.

The bullae can spread, and large surface areas of skin may become involved. Other clinical morphologies of skin disease have been described, including an erythema multiforme–like eruption, a pemphigoid-like eruption, and a lichenoid eruption that can mimic both graft-versus-host disease and lichen planus. These variants are infrequently seen. The combination of paraneoplastic pemphigus and an underlying malignancy has led to poor outcomes; this condition is refractory and very difficult to treat. The diagnosis is made by consistent clinical features in a patient with an underlying malignancy who also has serum autoantibodies against certain proteins, most frequently the plakin family of proteins.

Pathogenesis: Paraneoplastic

pemphigus is caused by circulating autoantibodies directed against various

intercellular keratinocyte proteins. The most commonly found antibodies are

directed against the plakin family of proteins, which include envoplakin and periplakin. Many other

autoantibodies have also been found. It is theorized that the underlying

neoplasm stimulates the cellular and humoral immune systems to form these

autoantibodies. The exact mechanism by which the tumor causes this to occur is

unclear.

Histology: Acantholysis

is the main histological feature on routine staining. Varying amounts of

keratinocyte necrosis are also appreciated. The blister forms within the

intraepidermal space. Routine staining cannot differentiate among the various

members of the pemphigus family of diseases. Direct immunofluorescence staining

in these diseases shows a fishnet staining pattern caused by intercellular

hemidesmosomal keratinocyte staining. Paraneoplastic pemphigus is much more

likely than any of the other pemphigus diseases to have a positive indirect

immunofluorescence staining pattern when rat bladder epithelium is used,

whereas the pattern when monkey esophagus epithelium is used is routinely negative. The opposite pattern is seen

with most other types of pemphigus. The unique histological and

immunofluorescence staining patterns seen in paraneoplastic pemphigus can lead

one to the diagnosis. Immunoblotting may also be done.

Treatment: Therapy needs

to be directed at the underlying neoplastic process. The overall outcome is

extremely poor. The 2-year survival rate has been estimated at 10%. Supportive

care to prevent superinfection of the skin is imperative. Immunosuppressants

are used to help decrease the blistering, but they may have deleterious effects

on the underlying neoplasm. If the underlying neoplasm can be cured, there is a

better chance that this disease will go into remission, although this does not

always happen. Corticosteroids, azathioprine, intravenous immunoglobulin

(IVIG), rituximab, plasmapheresis, bone marrow transplantation, and a host of

other therapies have been attempted with limited success.