SURGICAL TREATMENT OF

HYDROCEPHALUS

Transient

hydrocephalus can be temporarily treated with an external ventriculostomy or

lumbar drain. These temporary drainage systems allow constant monitoring of the

amount and character of CSF drainage, which can be quite helpful in patients

with a limited neurologic examination. For obstructive hydrocephalus, the CSF

diversion must occur above the blockage. In preterm infants, temporary

treatment of symptomatic hydrocephalus is achieved with a ventriculosubgaleal

shunt that drains the CSF into a subgaleal pocket or into a ventricular access

device that has a reservoir to tap to remove CSF. Once the preterm infant

achieves an adequate size, a more permanent CSF diversion procedure is

performed, if needed.

Endoscopic

procedures for CSF diversion include endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV),

cyst fenestration, choroid plexus coagulation, and other procedures. The

success of these procedures depends on multiple factors, including patient

selection and specific anatomic details. The primary benefit of endoscopic

procedures is the avoidance of implantation of shunt components that may later

malfunction, become infected, or induce shunt dependence. Endoscopic procedures

for CSF diversion can have late failure, and all patients after endoscopic

procedures continue to require chronic neurosurgical supervision similar to

patients with shunts.

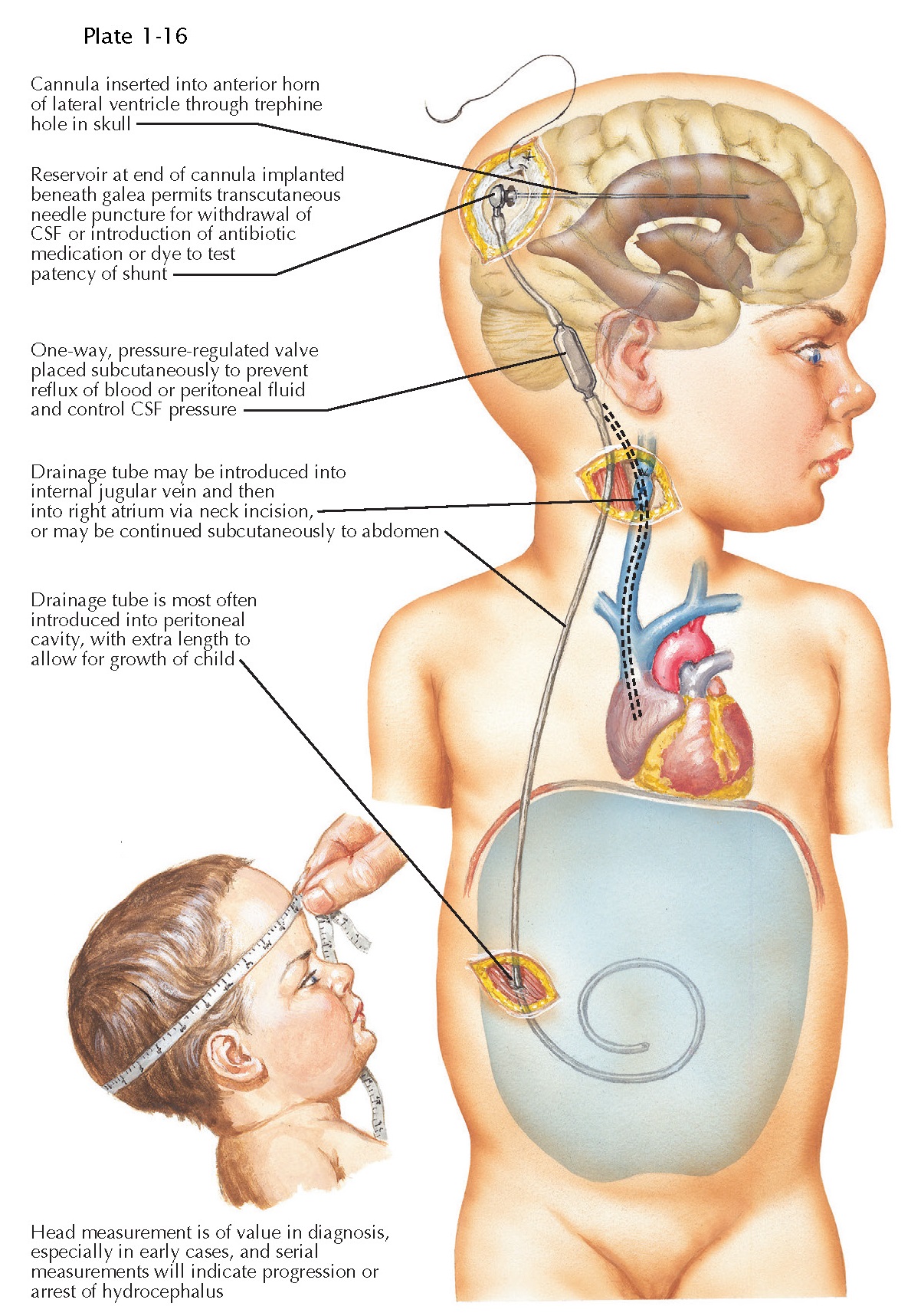

The

most common shunt system used is a ventriculoperitoneal shunt with a valve.

Shunt components are made from Silastic material, and some are

antibiotic-impregnated to decrease the risk of infection. The ventricular

catheter tip is targeted to the frontal horn of a lateral ventricle from either

a frontal or parieto-occipital trajectory. As the catheter exits the skull in

the subcutaneous space, it is connected to a valve. Some surgeons use an

intervening reservoir. The goal of the valve is to minimize overdrainage and

subsequent collapse of the ventricular system and formation of life-threatening

subdural hematomas. Various types of valves have been devised; none among them

has been proved superior in a well-designed multicenter trial. Shunt tubing can

also contain a valve at the distal tip. The subcutaneous distal shunt tubing is

inserted into the peritoneal cavity, where the peritoneum absorbs the CSF back

into systemic veins. Adequate tubing is placed in infants to decrease the

chance that a lengthening procedure will be required. Alternate distal tubing

sites include the right atrium or the pleural cavity. Lumboperitoneal shunts

are used in select patients. Occasionally, it is necessary to obtain CSF from a

patient with a shunt or to inject antibiotics or chemotherapy into the

ventricular system instead of via a lumbar puncture. Rarely, contrast material

may also be injected to identify loculations within the ventricular cavity. Any

manipulation of a shunt by a non-neurosurgeon

should be performed only in direct collaboration with a neurosurgeon.

The

long-term success of the CSF diversion procedure depends upon the continued

patency of the shunt or endoscopic opening. Failure of an endoscopic

fenestration can lead to the same symptoms and signs of neurologic decline as a

shunt failure. Once shunted, patients who may have previously absorbed a portion

of their CSF may become completely dependent on the shunt for CSF diversion.

The clinical presentation of a patient with failure of the CSF diversion

procedure may or may not mimic the symptoms at the

time of the diagnosis of hydrocephalus and initial treatment. The symptoms and

signs of failure and period of illness may depend on the type of failure, the

etiology of hydrocephalus and the patient’s age. The most common cause of shunt

malfunction is proximal catheter occlusion. Many patients with CSF diversion

failure will present with recurrence of ventriculomegaly. Of importance, 10% to

20% of children presenting with a shunt malfunction will have no apparent

change in the ventricular size compared with a baseline

imaging study.