Diaphragmatic Hernia

|

| SITES OF DIAPHRAGMATIC HERNIAS AND HERNIATION OF ABDOMINAL VISCERA |

Diaphragmatic hernia in the newborn is a not uncommon defect and seems to be reported increasingly, in one to four neonates per 10,000 births. This probably reflects earlier diagnosis and more prompt treatment rather than increased incidence. If the diaphragmatic defect is not surgically repaired, most of these infants die within the first month of life as a result of respiratory compromise.

The

most usual site of a congenital diaphragmatic hernia is the foramen of Bochdalek

in the posterolateral portion. Herniation most often occurs in the left side

and usually involves the stomach and the bowels. Right-sided hernias are rare

and may contain the liver. Less common hernias occur at the esophageal hiatus

and at the foramen of Morgagni in the retrosternal portion of the diaphragm.

Herniation through these latter defects usually does not produce severe

respiratory distress. Diaphragmatic eventration must be distinguished

from diaphragmatic herniation. The former refers to elevation of a portion of

the diaphragm that is thin and membranous due to incomplete muscularization.

The diaphragm in this case forms a sac that covers abdominal contents that are

displaced into the thorax. In rare cases, the diaphragm may completely or

partially fail to develop (diaphragmatic or hemidiaphragmatic

agenesis). The cause of congenital diaphragmatic hernia has not been

clearly elucidated; most occur sporadically. Failure of normal closure of the

pleuroperitoneal folds during the fourth to tenth weeks following fertilization

appears to be the initial step in formation of these hernias; genetic or

environmental factors are believed to trigger disruption of mesenchymal cell

differentiation during formation of the diaphragm, however.

Most

cases of congenital diaphragmatic hernia are diagnosed prenatally on routine

ultrasound screening at approximately 24 weeks of gestation. Visualization of a

chest mass with or without mediastinal shift is suggestive of a diaphragmatic

hernia. Fetal MRI can confirm the finding and estimate lung volumes, as well as

identify associated anomalies, which frequently occur with diaphragmatic

hernias. Fetal genetic studies should also be performed. In utero therapy is

investigational at this time and involves fetal tracheal occlusion, which

averts pulmonary hypoplasia and pulmonary hypertension by

increasing transpulmonic pressure. The birth should take place at a tertiary

care center via vaginal delivery induced at term.

Although

routine prenatal ultrasound examination is able to identify most congenital

diaphragmatic hernias, the diagnosis may not be made until after delivery. The

characteristic signs include a barrel-shaped chest with a left-sided

respiratory lag (if the hernia is on the left, as it is in

most instances) and a small and frequently scaphoid abdomen. The heart is

displaced to the right, often to an extreme degree. Breathing sounds are absent

over the left chest and are heard only over the upper right thorax portion,

where they are harsh in character. Gas fills the herniated bowel usually only

later, so that the percussion sounds over the chest are not necessarily

tympanitic directly after birth. Auscultatory findings, suggestive of

peristaltic movements in the chest, may be present but

are not reliable. Some infants, able to compensate for the presence of

abdominal viscera in the chest, exhibit signs and symptoms only when the

gas-filled intestines cause a greater mediastinal shift. Though the diagnosis

can be made on physical findings alone, chest x-ray confirms the clinical

impression, except when the severity of the infant’s respiratory dis- tress

does not allow time for such a procedure.

Once

the diagnosis of a diaphragmatic hernia is made, the management encompasses

preoperative medical management followed by surgical repair. Aggressive

preoperative medical management has improved survival rates to well over 90%

and involves ventilatory support after immediate endotracheal intubation. Use

of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation is reserved for infants who fail to

respond to conventional ventilatory support. Echocardiography is performed to

evaluate pulmonary hypertension and identify underlying cardiac anomalies. The

circulatory system is maintained by administration of fluids and inotropic

agents. To avoid additional distention of the abdominal viscera, nasogastric

tube placement before anesthesia is recommended. Premature infants with

respiratory distress syndrome should receive surfactant therapy.

In

the past, surgical repair of these types of hernias was considered an emergency

and infants underwent surgery shortly after birth. It is now accepted that

emergent surgery is not necessary, and the timing of surgical repair depends on

the severity of pulmonary hypoplasia and pulmonary hypertension. Infants requiring

minimal support with no evidence of pulmonary compromise can undergo surgical

repair within 72 hours. In infants with some degree of pulmonary hypoplasia and

reversible pulmonary hypertension, surgery should be delayed until pulmonary

compliance improves and pulmonary hypertension is reversed.

|

| THORACIC APPROACH TO REPAIR OF DIAPHRAGMATIC HERNIA |

Surgical

repair of the diaphragmatic hernia can be performed using an abdominal or a

transthoracic approach via either open or minimally invasive techniques.

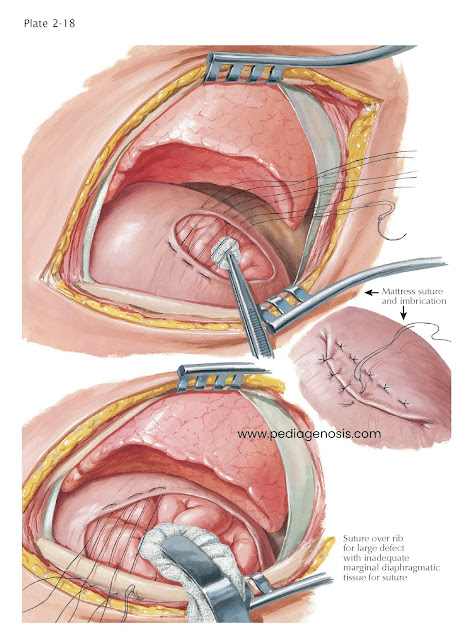

The

repair of the diaphragmatic defect may be accomplished by primary closure;

however, larger defects often need a synthetic patch repair to allow a

tension-free closure. The abdominal cavity may also be too small and

underdeveloped to accommodate the intestine and permit closure of the abdominal

wall muscle and fascial layers. In such cases, a temporary abdominal wall silo

or mobilization of abdominal wall skin flaps may be necessary

to allow for gradual visceral reduction and concomitant abdominal cavity

expansion, so that a staged closure of the abdominal wall is possible.

Complications following repair can be seen immediately after surgery with persistent pulmonary hypertension or can occur late with chronic respiratory disease, recurrent hernia, patch infection, spinal or chest wall abnormalities, and gastroesophageal reflux.