PLEURAL EFFUSION IN MALIGNANCY

The diagnosis of a malignant pleural effusion is established when malignant cells are identified in pleural fluid or in pleural tissue. However, in about 10% to 15% of patients with a known malignancy and a pleural effusion, malignant cells cannot be identified; these effusions are termed paramalignant effusions. Paramalignant effusions develop from local effects of the tumor (lymphatic obstruction), systemic effects of the tumor (pulmonary embolism), and complications of therapy (radiation pleuritis and effects of chemotherapy). Although carcinoma from any organ can metastasize to the pleura, lung cancer and breast carcinoma are responsible for approximately 60% of all malignant pleural effusions. Ovarian and gastric carcinoma are the third and fourth leading cancers to cause malignant effusions; lymphomas account for approximately 10% of all malignant pleural effusions.

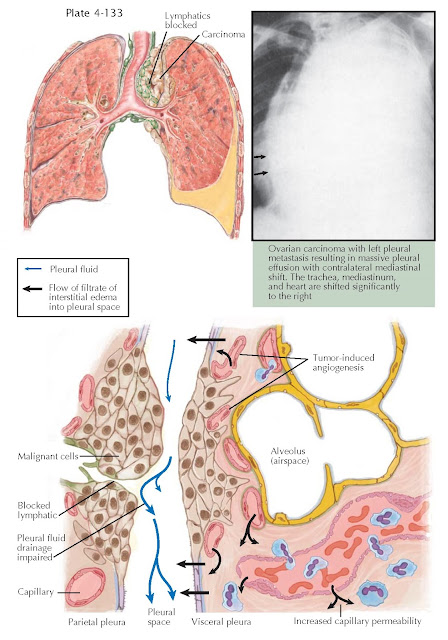

Impaired lymphatic drainage, tumor-induced angiogenesis,

and increased capillary permeability from vasoactive cytokines and chemokines

contribute to the pathogenesis of the malignant effusion.

Patients with malignant pleural effusions most commonly

present with dyspnea, with the degree dependent on the volume of pleural fluid

and the underlying lung disease. A therapeutic thoracentesis provides temporary

relief of dyspnea in most patients.

With lung cancer, the pleural effusion is typically

ipsilateral to the primary lesion. With a non-lung primary lesion, there appears

to be no ipsilateral predilection, and bilateral effusions are common. When a

pleural effusion is massive, occupying the entire hemithorax, there is usually

contralateral mediastinal shift, and malignancy is the cause in approximately

70% of patients. When there is complete opacification with absence of

contralateral shift, the scenario suggests carcinoma of the ipsilateral

mainstem bronchus (the density on chest radiographs represents complete lung

collapse and a smaller pleural effusion); the initial diagnostic test should be

bronchoscopy with biopsy of the endobronchial lesion.

A malignant effusion may appear serous, serosanguineous,

or grossly bloody. The total nucleated cell count normally ranges from 1500 to

4000/L and consists of lymphocytes, macrophages, and mesothelial cells. These

effusions are predominantly lymphocytes (50%-75% of the nucleated cells) in

about half of patients. Neutrophils tend to be less than 25% of the total

nucleated cells. The prevalence of pleural fluid eosinophilia in malignant

effusions ranges from 8% to 12%; therefore, finding pleural fluid eosinophilia

(eosinophils 10% of the total nucleated cells) should not be considered a

predictor of benign disease. The pleural fluid protein and lactate dehydrogenase

levels are typically in the exudative range. The pleural fluid pH is less than

7.30, and the glucose is less than 60 mg/dL in approximately 30% of patients at

presentation. A low pH and glucose level suggests significant involvement of the

pleura. This inhibits glucose movement into the pleural space and efflux of the

end products of glucose metabolism, CO2 and lactic acid, resulting

in pleural fluid acidosis. A low pH predicts decreased survival and a poorer response to pleurodesis.

The yield from diagnostic testing of a malignant

pleural effusion correlates directly with the extent of disease. Pleural fluid

cytology is more sensitive than percutaneous pleural biopsy because the latter

is a blind sampling procedure. Thoracoscopy by an experienced operator will

diagnose up to 95% of malignant pleural effusions. The diagnosis of a malignant

pleural effusion signals a poor prognosis; therefore, with lung and gastric

carcinoma, the survival is typically a few months.

With breast cancer and lymphoma, a response to

chemotherapy may result in a longer survival. In patients unresponsive to

chemotherapy, relieving breathlessness by controlling the malignant pleural

effusion substantially improves quality of life. If the lung is expandable,

pleurodesis with talc is an option. With an unexpandable lung, placing an

indwelling catheter as an outpatient with home drainage can manage the

patient’s breathlessness.