|

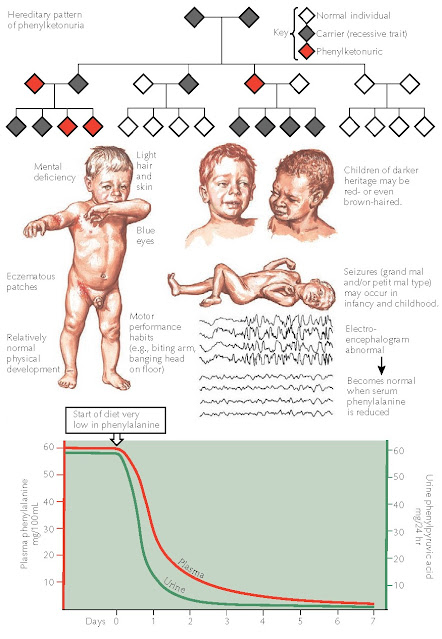

| NORMAL AND ABNORMAL METABOLISM OF PHENYLALANINE |

Phenylalanine is an essential amino acid that serves as a substrate for many different biochemical pathways. Two end products that use phenylalanine as their precursors are melanin and epinephrine. Under normal physiological and biochemical environments, any excess amount of phenylalanine is converted into tyrosine by the liver and used for a host of biochemical processes including protein synthesis. In patients with phenylketonuria, the enzyme in the liver that converts phenylalanine into tyrosine is completely absent. This inborn error of metabolism is one of the most thoroughly researched disease states. With early detection and therapy, the severe sequelae of phenylketonuria can be avoided. Screening is performed soon after birth for all children in the United States and in most of the world. Children born in regions with poor medical infrastructure and no testing are at risk for the disease. Once the disease symptoms have appeared, therapy usually cannot reverse the damage that has been done. Phenyl-ketonuria is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, but many genotypes have been described, and many mutations in the responsible gene have been reported. The defect is located on the long arm of chromosome 12, where the PAH gene encodes the protein, phenylalanine hydroxylase.

Clinical Findings: Phenylketonuria occurs in approximately 1

of every 10,000 births in the United States, with the Caucasian population

being at highest risk. Worldwide, the Turkish population has the highest rate,

1 per 2500 newborns. Both genders are affected equally. Infants appear normal

at birth. The small load of phenylalanine that is derived from the maternal

source in utero is typically not high enough to cause any symptoms or signs of

phenylketonuria. Soon after birth, the first symptoms appear as the neonate,

lacking the PAH enzyme, rapidly begins to accumulate phenylalanine in serum and

tissues. Other biochemical pathways are enacted to try to rid the body of the

excess phenylalanine, but these make matters worse. The degradation metabolites

that are produced from various deamination and oxidation metabolic modification

reactions can cause end organ damage. Phenyl-lactic acid, phenylpyruvic acid,

and phenylacetic acid are the main byproducts. Because of these byproducts, the

urine takes on a characteristic “mousy” odor.

Affected

neonates have blond hair and a generalized hypopigmentation. Children with

darker skinned parents often have a lighter skin tone and lighter hair and eye

coloration than either parent. Most have blue eyes. Evidence of early-onset

dermatitis that may appear as atopic dermatitis is often present. Other skin

changes that have been described include sclerodermoid changes of the trunk and

upper thighs.

The

most dreaded sequela of phenylketonuria is the profound brain damage that can

occur secondary to the elevated levels of phenylalanine. The neonatal brain is

easily damaged by excessive levels of this amino acid. Global brain damage is

caused by phenylalanine, and the damage is typically irreversible. This is the

reason that screening tests are performed on neonates. Mental retardation,

seizures, and tremors are common effects of phenylketonuria. Seizures can be of

the grand mal or petit mal type and occur in infancy or childhood. The seizures

are reversible once a low-phenylalanine diet is undertaken. The

electroencephalogram (EEG) of all infants and children with phenylketonuria

shows abnormal results. As the child grows, the mental deficiencies begin to

become more apparent. Physical growth and physical maturation are unaffected.

Children tend to be hyperactive and are prone to develop self-mutilating

rituals such as biting themselves or banging their heads violently against

walls or floors. Tremors may be the only other neurological finding observed.

Laboratory

testing shows elevated levels of phenylalanine in the serum. Normal levels are

between 1 and 2 mg/dL, and those with untreated phenylketonuria have levels

greater than 20 mg/dL. Phenylpyruvic acid typically is not present in the urine

in appreciable amounts in the normal physiological state. In patients with

phenylketonuria, urine levels are elevated. The addition of ferric chloride to

the urine causes acidification of the urine, and a transient green

discoloration is produced.

All

neonates should be tested for phenylketonuria within the first day or two of

life as part of routine metabolic screening. This test can be followed up in 7

days if the initial test was performed within the first 24 hours of life or if

the initial test was positive. Testing is performed by the Guthrie inhibition

assay or by the McCamon-Robins fluorometric test. These tests are highly

accurate; levels greater than the normal value of 0.5 mg/dL are considered

suspicious, and levels greater than 2 to 4 mg/dL are diagnostic.

Histology: Findings on skin biopsy are nondiagnostic and are

rarely helpful in this disease. Biopsy specimens of the hypopigmented skin

appear normal. Those from areas of dermatitis show a nonspecific, spongiotic

dermatitis with a lymphocytic infiltrate.

Pathogenesis: Phenylketonuria is an autosomal recessive disorder of

the metabolism of phenylalanine. It is caused by a genetic defect in the long

arm of chromosome 12, which results in a nonfunctional phenylalanine

hydroxylase enzyme. Phenylalanine and its metabolites, via other metabolic

pathways, lead to the clinical signs and symptoms. Excessive phenylalanine

causes skin and hair hypopigmentation by direct inhibition of the tyrosinase

enzyme, which decreases the amount of melanin and other molecules that are

dependent on this enzyme pathway. Once the phenylalanine levels have dropped

below the threshold of tyrosinase inhibition, enzyme function returns to normal

and the pigmentary abnormalities resolve. Phenylalanine is directly toxic to

brain cells, resulting in severe central nervous system (CNS) abnormalities.

Numerous mutations of the PAH gene have been reported, making in utero

diagnosis very difficult.

Treatment: The most important aspect of therapy is to maintain a

low-phenylalanine diet. The goal should be to continue this diet lifelong,

because a subset of those who stop the diet early develop CNS disease. This is

especially true for women of child-bearing age. Women with deficiencies of

phenylalanine hydroxylase who become pregnant can cause irreversible brain

damage to their offspring if they do not control their phenylalanine level.

These women should stay on a strict phenylalanine-free diet and be managed by a

high-risk obstetrics team. Phenylalanine serum levels should be tested routinely

to make sure the gravid mother keeps her serum phenylalanine level below 5 to

10 mg/dL. Women who are considering getting pregnant should go on a

low-phenylalanine diet before conception and should be under the care of an

obstetrician. The diet is a prepared amino acid mixture. Strict elimination of

foods high in phenylalanine is required, including meat, eggs, fish, milk,

breads, and many other foodstuffs. The diet can be very difficult to follow for

even the most dedicated of individuals. The artificial sweetener aspartame must

also be avoided, because it is made up of aspartate and phenylalanine.

Approximately

50% of cases of phenylketonuria respond to the medication tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4,

sapropterin). BH4 has been found to help metabolize excess phenylalanine, and

its starting dose and maintenance dose are based on patient weight and response

to Therapy. Levels of phenylalanine must be measured over a few weeks to months

to determine the effectiveness of the medication. Those patients who

are helped may potentially be able to increase the amount of protein in their

diet.

|

| CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS, HEREDITARY PATTERNS, AND EFFECTS OF PLASMA AND URINARY LEVELS IN PHENYLKETONURIA |

During therapy, the skin disease, including discoloration of the hair and skin as well as dermatitis, disappears. The abnormal EEG pattern reverts to normal, and the patient’s urine returns to normal. Mental performance may always lag, and permanent damage may be sustained early in the course of the disease. Only mild behavioral improvements have been reported. Those children who were diagnosed before the onset of any abnormal symptoms and are maintained on a low phenylalanine diet do not develop any of the sequelae of the disease.