INJURY TO HIP

|

| ACETABULAR FRACTURES |

The acetabulum of the pelvis makes up the socket of the hip joint. It develops at the confluence of three epiphyseal junctions between the ilium, ischium, and pubis. The growth of the acetabulum occurs with the development of this triradiate cartilage, and its shape is influenced considerably by the shape of the femoral head with which it articulates. Acetabular injuries are not as common as other injuries to the hip joint, and most result from forces generated by the femoral head against the confines of the acetabular cup. Fractures tend to occur in younger persons and involve greater violence than the typical femoral neck or intertrochanteric fracture.

Acetabular injuries range from simple avulsions of the

periphery of the acetabulum to explosions of the hip socket (see Plate 2-67). When the acetabulum fractures, the femoral head is usually dislocated

or subluxated in relation to the part of the acetabulum that remains intact.

The displacement may be anterior, central, or posterior. After reduction, an

incongruence often exists between the femoral head and the acetabulum.

Acetabular fractures are classified as simple and associated. Simple fracture

patterns are further categorized as fractures of the anterior wall, anterior

column, posterior wall, and posterior column and transverse fractures.

Associated fracture patterns comprise fractures of the posterior wall and

posterior column, transverse fractures with posterior wall fractures, T-shaped

fractures, fractures of both columns, and fractures of the anterior wall or

column with an associated posterior hemitransverse fracture.

Patients with minimally displaced fractures of the acetabulum

or those who cannot, or elect not to, undergo surgical treatment are treated

with nonoperative measures. Initially, the patient is placed in traction until

the acute reaction of the fracture subsides. Then the hip is moved through a

range of flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction, either by a physical

therapist or with the use of a continuous passive motion machine. Once these

movements are achieved comfortably, the patient is mobilized using crutches,

with minimal weight bearing on the injured side. Radiographs are taken

frequently to assess the healing of the fracture and to check for residual

displacement of the femoral head.

CENTRAL FRACTURE OF ACETABULUM

Patients with severe central fracture dislocations of

the acetabulum who cannot be treated with surgery are managed with more complex

traction arrangements (see Plate 2-68). First, skeletal traction is applied

with a pin through the distal femur or proximal tibia to establish a normal

relationship between the superior femoral head and the dome of the acetabulum.

About one sixth of the

patient’s body weight is applied through the traction mechanism to restore the

injured limb to its normal length. After this maneuver, a radiograph is

obtained to assess the relationship of the femoral head to the intact

acetabulum. If subluxation of the femoral head persists, lateral traction,

applied with a sling or with a pin placed in the femur distal to the greater

trochanter, is used to extricate the femoral head from the pelvis.

Traction is maintained for 6 to 8 weeks. Weight bearing on the injured lower

limb is limited for at least 3 to 4 months from the time of injury. Residual

subluxation may occur in the same direction as the original displacement.

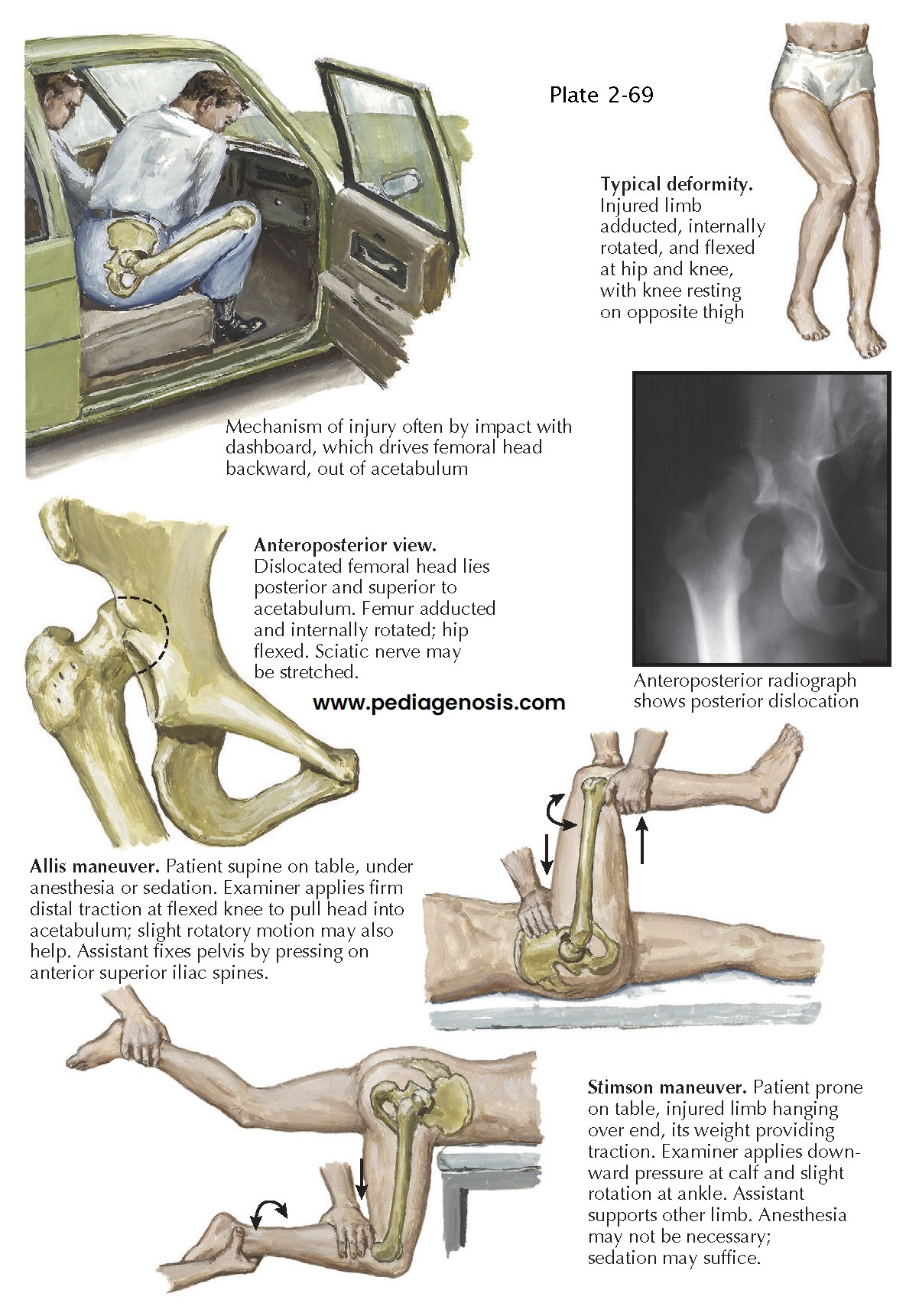

POSTERIOR DISLOCATION OF HIP

Posterior dislocations of the hip have become more

common as the occurrence of high-energy trauma has increased (see Plate 2-69).

The classic mechanism of injury is the impact of the dashboard against the

flexed knee during a head-on motor vehicle collision. The dashboard collapses,

striking the knee and driving the femoral head out of the acetabular socket.

Generally, the resulting posterior dislocation of the hip is not an isolated

injury; multiple injuries of the lower limb often occur, including fractures of

the patella and femoral shaft and injuries to the posterior cruciate ligament.

|

| ACETABULAR FRACTURES (CONTINUED) |

Pure dislocations of the femoral head occur with the

hip adducted and flexed. In this position, the force is concentrated against

the soft tissues of the hip joint capsule rather than the bony architecture of

the posterior acetabulum. Indentation fractures of the femoral head

occasionally occur, as do abrasions of the articular cartilage. Because of its

close proximity to the posterior aspect of the hip joint, the sciatic nerve (especially

the peroneal division) is injured in 8% to 20% of patients with posterior

dislocation or posterior fracture dislocation of the hip. Sciatic nerve injury

is more common with fracture-dislocations than with pure dislocations.

When the dislocation of the hip is posterior, the

major blood supply to the femoral head is injured. Avascular necrosis of the

femoral head, one of the more common complications of this injury, appears to

be related to the amount of time the femoral head remains dislocated from the

acetabulum.

Posterior dislocation of the hip results in a classic

posture: the lower limb is flexed at the hip joint, adducted, and internally

rotated. Careful physical examination also reveals shortening of the limb. Many

patients report a feeling of fullness in the buttocks. A neurologic evaluation

of the limb must be performed, with emphasis

on the musculature innervated by the peroneal division of the sciatic nerve.

Radiographs of the pelvis and hip reveal the absence

of the femoral head from its normal articulation in the acetabulum. The

displaced head usually appears smaller than the femoral head on the uninjured

side and in a position proximal to the acetabulum.

Radiographs are important for determining both the

extent of bone injury to the hip socket and any associated fractures.

In posterior dislocation of the hip with no associated

sciatic nerve injury, the hip should be reduced within 12 hours of injury.

Prompt reduction helps to minimize the development of avascular necrosis of the

femoral head. Dislocations

with associated sciatic nerve injury are acute emergencies and must be reduced

to relieve extrinsic pressure on the nerve and lessen the risk of permanent

sciatic nerve palsy.

In patients with multiple injuries, the most common

method of closed reduction of a posterior dislocation of the hip is the Allis

maneuver. The maneuver is performed with the patient supine and allows further

evaluation of associated injuries to the abdomen, chest, and airway that would

be difficult to perform with the patient in a lateral or prone position. With

an assistant stabilizing the pelvis, the physician applies gentle traction to

the lower limb in the line of the deformity. After traction has been applied,

the hip is gently flexed 90 degrees while gentle internal and external rotation

is applied until reduction is achieved. When it occurs, the reduction can be

felt by both the physician and the assistant.

If the dislocation is an isolated injury, the Stimson

gravity reduction maneuver can be used. The patient is placed prone and the

injured hip flexed over the end of the examining table. An assistant stabilizes

the pelvis by pressing down on the sacrum or by extending the uninjured limb.

The physician flexes the involved hip and knee 90 degrees and applies gentle downward

pressure behind the flexed knee. As pressure is applied, gentle internal and

external rotation is added. As in the Allis maneuver, both the physician and

the assistant can feel the reduction when the femoral head relocates into the

acetabulum.

|

| POSTERIOR DISLOCATION OF HIP |

After reduction, it is extremely important to reassess

the neurologic status of the injured limb, focusing on the function of the

sciatic nerve and its peroneal division. If sciatic nerve dysfunction is now

apparent, surgical exploration of the nerve should be considered. Radiographs

and CT scans should be examined for evidence of joint space widening or for the

presence of small bone fragments within the joint that might prevent congruence

between the femoral head and the acetabulum.

After successful reduction, the limb is placed in light skin traction to allow

the injured hip to rest. When the local reaction to the injury sub- sides, the

patient can be mobilized and begin gentle active range-of-motion exercises,

including extension, flexion, abduction, and adduction.

Guidelines for weight bearing after this injury are

not well established and remain controversial. Generally, early motion of the hip is promoted but weight bearing

is delayed. If evidence of avascular necrosis develops, weight bearing is

postponed even longer to prevent collapse of the femoral head. Although

recurrence of posterior dislocation or subluxation of the hip is rare,

post-traumatic osteoarthritic changes of the hip are not uncommon. Follow-up

should continue for at least 2 years to detect any arthritic or necrotic changes.

About 10% to 15% of traumatic dislocations of the hip

are anterior dislocations, either the superior type or the more common

obturator type (see Plate 2-70). Anterior dislocation occurs when the hip is

abducted, externally rotated, and flexed and the knee strikes a fixed object.

Either the neck of the femur or the greater trochanter levers the head of the

femur out of the acetabulum through a disruption of the anterior hip capsule.

As the femoral head leaves the anterior aspect of the acetabulum, transchondral

or indentation fractures of the femoral head can occur. Since the introduction

of CT, the incidence of this type of fracture has been shown to be much greater

than previously thought.

The characteristic clinical appearance is the limb

flexed at the hip, abducted, and externally rotated. In assessing the

neurovascular status after an obturator dislocation, the examiner must pay

special attention to the presence of an injury to the obturator nerve resulting

in paresis of the hip adductor musculature. Similarly, in the superior

dislocation, the femoral nerve, artery, or vein can be damaged and must be

assessed before reduction attempts are made. Radiographic evaluation of the

injury should include anteroposterior and Judet views (oblique at 45 degrees)

of the pelvis to help delineate associated injuries of the acetabulum, femoral

head, and femoral neck.

|

| ANTERIOR DISLOCATION OF HIP, OBTURATOR TYPE |

The Allis maneuver is generally recommended for

obturator dislocations. Strong intravenous analgesics or spinal anesthetics are

given to provide adequate muscle relaxation. If closed reduction is not

successful, open reduction is required. An anterior iliofemoral approach allows

identification and treatment of the obstruction to the dislocation.

After reduction, new radiographs are taken to

determine the extent of associated injuries to the femoral neck, acetabulum, or

femoral head. Polytomography or CT may demonstrate a nondisplaced fracture of

the femoral head or indentation fracture resulting from impingement of the

femoral head against the acetabulum. Reassessment of the neurovascular status

of the limb distal to the hip is also important. Post-traumatic osteoarthritis

requiring later reconstructive surgery eventually develops in one third of patients.

Avascular necrosis may also be a residual

complication. Recurrent dislocations are not common.

Postreduction care involves light traction with early

active range-of-motion exercises, including extension, flexion,

abduction-adduction, and rotation but avoidance of extremes of flexion,

abduction, and external rotation. Just when weight bearing should begin is not clear, and the available guidelines are not

consistent. Usually, as pain diminishes, the patient is allowed to begin weight

bearing using crutches for support. Weight bearing is gradually increased until

the support can be discarded. Follow-up should continue for at least 2 years to monitor for avascular necrosis or

post-traumatic osteoarthritis.

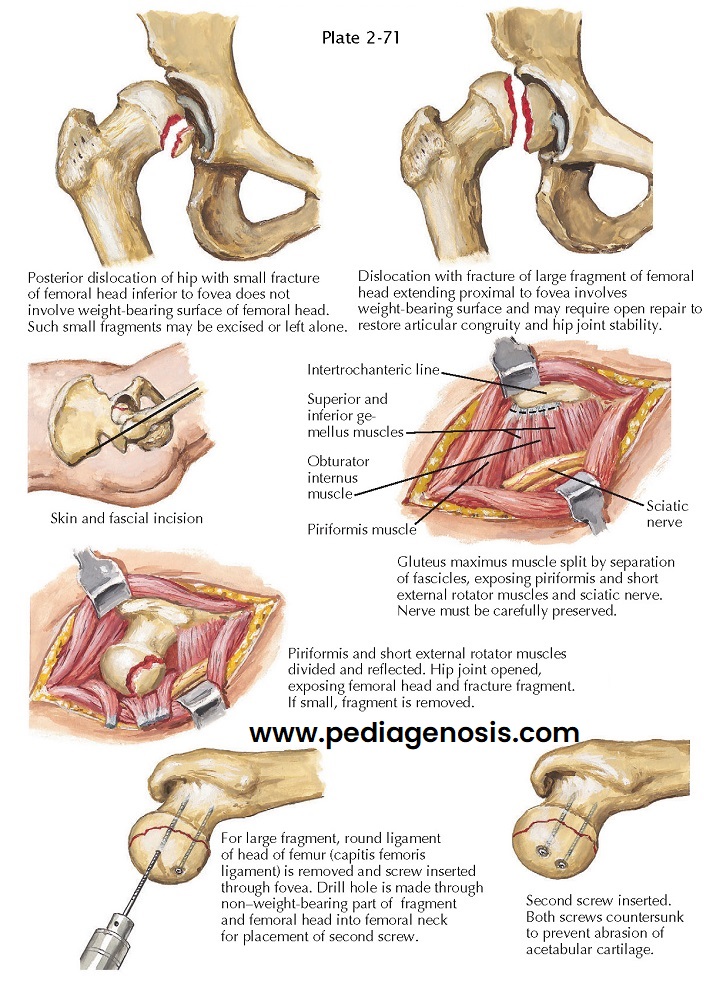

DISLOCATION OF HIP WITH FRACTURE OF FEMORAL HEAD

As posterior dislocations and fracture dislocations of

the hip have increased in frequency, associated femoral head fractures have

also become more common (see Plate 2-71). These injuries are

believed to occur with the hip flexed 60 degrees or less and in neutral

abduction. The force of the trauma drives the femoral head against the

posterosuperior portion of the acetabulum, resulting in the dislocation and

shear fracture of the femoral head.

Pipkin delineated four types of fracture dislocations

of the hip and assigned higher numbers to the injuries with the worst

prognoses. In type I injuries, fracture of the femoral head occurs inferior to

the fovea of the head of the femur. Type II injuries include a fracture that is

superior to the fovea. In type III injuries, a type I or type II fracture may

occur in association with a femoral neck fracture, and type IV injuries involve

a type I, type II, or type III injury in association with an acetabular

fracture.

|

| DISLOCATION OF HIP WITH FRACTURE OF FEMORAL HEAD |

Because these injuries are associated with posterior

hip dislocations, the neurovascular status of the limb must be determined and

radiographs of the hip, including anteroposterior and Judet views, obtained

before reduction is attempted. The posterior dislocation should be reduced as

soon as possible to minimize avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Reduction

can be performed using the maneuvers described for reduction of a simple

posterior dislocation of the hip. Careful evaluation must be made of the

reduction of the femoral head in the acetabulum and the reduction of the

fractured portion of the femoral head to the intact head. The femoral head must

be concentrically reduced in the acetabulum. The amount of step-off and gap

that exists at the fracture surface must also be determined.

In type I or II injury, the fragment of the femoral

head need not be removed as long as it does not impede hip motion and the hip

is congruently reduced and stable. If a congruent reduction was not achieved,

removal or internal fixation of the fragment to the remaining surface of the

femoral head should be considered.

After closed reduction, incongruence resulting in either an offset or gap

greater than 2 mm should be used as the criterion for open reduction or

excision of the fragment. As much as one third of the femoral head can be

removed, but many surgeons prefer internal fixation of fragments of this size.

In type III and IV injuries, the adequacy of the reductions of the femoral head fracture and dislocation are assessed first; then the reduction of the femoral neck or the acetabulum or both must be evaluated. Displaced fractures of the femoral neck may require internal fixation, and severe displacement may necessitate total hip replacement. Internal fixation of acetabular injuries should be considered if this will optimize the anatomic reconstruction of the hip joint.